Pronounced GAS•TROW•SKEE•SIS, this is an abnormality that occurs during fetal development. Gastroschisis is a centrally located, full thickness abdominal wall defect ___ that results in the incomplete formation of the abdominal wall. This causes the intestines to exit beside the umbilicus, and the umbilicus remains intact and located just to the left of the defect. The baby’s bowel pushes through this hole (on the right side of the belly button) and proceeds to develop outside of the body. This birth defect can vary in size—anywhere from a small portion of the intestine to a significant defect encompassing the intestine, pancreas, liver, uterus, fallopian tubes, etc. Gastroschisis is usually an isolated defect and is not typically associated with other abnormalities or malformations.

What Causes Gastroschisis?

The exact cause is not known. It does not appear to be inherited. Having one baby with gastroschisis does not make it more likely that you would have another baby with the condition.

In nursing school, you learn that this is a very rare condition. However, in the NICU this diagnosis is more common than you think. It occurs in about one in every 2,000 babies and develops in early pregnancy—around the fourth through eighth week. It is possible for gastroschisis to be detected in the third month of pregnancy. However, we most often perform evaluations for it at 20-24 weeks. It is most commonly diagnosed by ultrasound around weeks 18-20 of pregnancy.

An important part of the exam is determining whether the condition is gastroschisis or omphalocele. These conditions can sometimes look similar on an ultrasound. In omphalocele, a sac from the umbilical cord covers and protects the intestines that are outside of the baby’s body.

In gastroschisis, because the intestines are not covered in a protective sac, they are exposed to irritating amniotic fluid. Because the development of this disorder happens very early in the pregnancy, prolonged exposure to amniotic fluid causes the bowel to become thick, swollen, inflamed, and sometimes twisted. Once your baby is born, the internal organs will be exposed to air and remain unprotected. This makes the bowel more susceptible to infection and causes your baby to lose heat and fluids very rapidly.

Sounds painful. Will this hurt my baby?

The abnormality itself does not hurt. However, the process of reducing the bowel and the surgery is very uncomfortable. It will require that the baby be heavily medicated, sedated, and paralyzed with pain medication.

Okay, so your baby has gastroschisis… now what?

Luckily, this is a very treatable condition through surgery and reduction!

After your tests are complete and the diagnosis is confirmed, your healthcare team will discuss the extent of the baby’s condition and its impact on the rest of the pregnancy. They will also cover medical treatments that might be needed right after birth as well as the long-term prognosis. Overall, babies born with gastroschisis have an excellent prognosis with a survival rate of close to 100%. The team will also create a plan for the remainder of your pregnancy and will talk to you about what to expect after delivery. Your doctor may suggest a Cesarean section due to the potential risks and trauma to the bowel via squeezing through the birth canal.

Typically, after your baby is born, the pediatric gastroenterologist surgeon performs a “primary” repair by manually (and gently) pushing the bowel back into the abdominal cavity. When possible, this surgery is performed the day your baby is born.

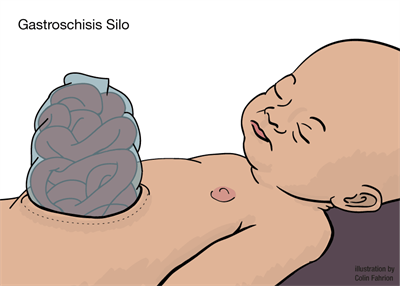

However, in a more severe or complicated case of gastroschisis, this won’t happen all at once. A “staged” repair is a slow, gradual process. The surgeon must be very careful because it can alter the pressure within the cavity, potentially risking respiratory distress and elevated blood pressures. Normally, the bowel will be reduced little-by-little on a day-to-day basis, depending on how well the baby tolerates it. This may take place over several days or weeks. The part of the bowel that remains outside of the body during this time is placed in a plastic contraption called a “silo” (pronounced sigh•low). A silo is a “bowel bag” that attaches to a bar that suspends above the baby so that the exposed organ can slowly enter into the body via gravity. Every day, the silo is tightened and some of the bowel is gently pushed inside the baby’s abdomen. When all of the bowel is inside, the belly is closed. This bag is very important because it holds in moisture and heat as well as protects your baby’s exposed bowel from external sources of contamination, trauma, or infection.

Nursing responsibilities before surgery include:

Hourly silo assessments (checking to make sure the dressing is clean/dry/intact)

Hourly inspection of abdomen. Necrotic bowel will appear discolored or block and will be visible superficially through the abdomen.

Auscultating for bowel sounds. Because of the intestinal abnormality, development of appropriate peristalsis and effective absorption is significantly delayed.

Hourly vitals (including temperature since this is a high risk for infection).

Maintaining the infant NPO. Your baby will not be able to eat before or after surgery for a while. IV fluids will provide your baby with the proper hydration and nourishment. TPN and Lipids supply the perfect blend of vitamins, minerals, sugar, protein, calories, and fats for your little one.

Maintaining infant on his/her right side to avoid strangulation due to reduction of blood flow.

Decompress stomach via low intermittent suction using an Anderson tube. Replace high volumes of output as needed to prevent dehydration.

Until surgery, we will cover your baby’s bowel with moist, warm, sterile gauze.

Nursing responsibilities after surgery include:

Frequent respiratory exams. These babies may have trouble breathing and will need respiratory support. Your baby may not be able to breathe effectively on his own due to the increased pressure on the diaphragm from the bowel that is now in the abdominal cavity.

Hourly pain and sedation assessments. This ensures your baby is properly medicated.

Keeping pressure off the diaphragm. We will place a gastric tube through the baby’s nose—which is a nasal gastric (NG) tube—or mouth—which is an oral gastric (OG) tube. We will apply suction to this tube to keep the stomach empty and decompressed in order to not cause any more pressure on the diaphragm.

Maintaining IV access. Several IV medications will be administered following surgery. These include antibiotics to prevent infection, pain medications for comfort, and IV fluids until your baby is ready to take food by mouth.

Hourly bowel/GI assessment.

The hardest part of recovery for babies with gastroschisis is learning to eat and tolerating food. Your baby’s bowel has developed outside of the body. It needs to heal and adjust to functioning normally inside the body. Because of that, babies with gastroschisis commonly have feeding challenges the first few weeks of life. Before we introduce breast milk or formula, we wait for signs from the baby that the bowels are beginning to work. These signs include:

Active bowel sounds

Spontaneous passing of stool

A decrease in the drainage coming from the tube in the baby's stomach

Note: In some cases of gastroschisis, a bowel resection may be necessary. This is a surgery that is needed when a portion of the bowel is extremely damaged and necrotic. The dead bowel that does not function properly is removed and an ostomy is placed. This is an opening that allows stool to pass out of the body and into a bag. With bowel resection surgery, there is a potential risk of developing short gut syndrome.

Questions? Comments? Concerns? Was your baby diagnosed with gastroschisis? Let me know! <3